On the world stage, the grounding of the supertanker TORREY CANYON on Pollard’s Rock in the Seven Stones reef between Cornwall and the Scilly Isles is more significant than the 1989 EXXON VALDEZ oil spill. The TORREY CANYON was one of the first tankers large enough (120,000 tons capacity) to be designated a supertanker. It was also the first loaded supertanker to spill its entire cargo.

The grounding and breakup of the supertanker SS TORREY CANYON has had an international legal and environmental legacy. At the time it was the world’s worst oil spill, causing an environmental disaster with an estimated 94,000 –164,000 tons of crude oil spilt. It remains the worst spill in UK history.

On her final voyage, TORREY CANYON left the Kuwait National Petroleum Company refinery at Mina Al-Ahmadi, Kuwait, with a full cargo of crude oil, on 19 February 1967. The ship had an intended destination of Milford Haven in Wales. On March 14, she reached the Canary Islands.

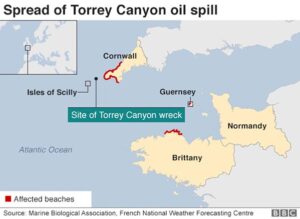

Following a navigational error, the vessel struck Pollard’s Rock on Seven Stones reef between the Cornish mainland and the Isles of Scilly on 18 March 1967 (The Master of the super tanker took a dangerous short cut to catch a tide. His reckless decision was based on a culture of greed, not safety, and that is where the underlying and still on-going problem lies).

The tanker did not have a scheduled route and as such lacked a complement of full scale charts of the Scilly Islands. To navigate the region, the vessel used LORAN, but not the more accurate Decca Navigator. When a collision with a fishing fleet became imminent, there was some confusion between the Master and the helmsman as to their exact position. Significant further delay arose due to uncertainty as to whether the vessel was in manual or automatic steering mode.

After salvage efforts failed and the oil flow increased, the British Government decided to bomb the ship in an attempt to burn the oil. This was a radical decision because the wreck was outside the three-mile territorial sea limit prevalent at that time. The Royal Air Force had difficulty hitting the ship, so the Royal Navy sent its planes in.

They succeeded in striking the ship, but the bombs did not ignite the oil, which washed up on beaches throughout the British Isles and France. Worst hit were the Cornish beaches of Marazion and Prah Sands, where sludge was up to a foot deep. Up to 70 miles (113km) of beaches were seriously contaminated.

The actions of the British Government were subsequently ratified with the adoption of the International Convention relating to Intervention on the High Seas in cases of Oil Pollution Casualties, 1969. Liability of ship owners for such events was codified in the International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage, 1969. By raising the awareness of both the industry and the public concerning the threat of maritime pollution, the disaster was also a major factor in development of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973.